Moroccan Jews: Saving a Shared Heritage

CHIARA LUTTERI

INSIGHT #5 • JUNE 2020

“Shalom Alaykoum, Salam Lekoulam”: with this bizarre mélange of Jewish and Arabic salutations, visitors of the memorial museum of Essaouira are welcomed into one of the most important places for the preservation of the Jewish-Moroccan memory.

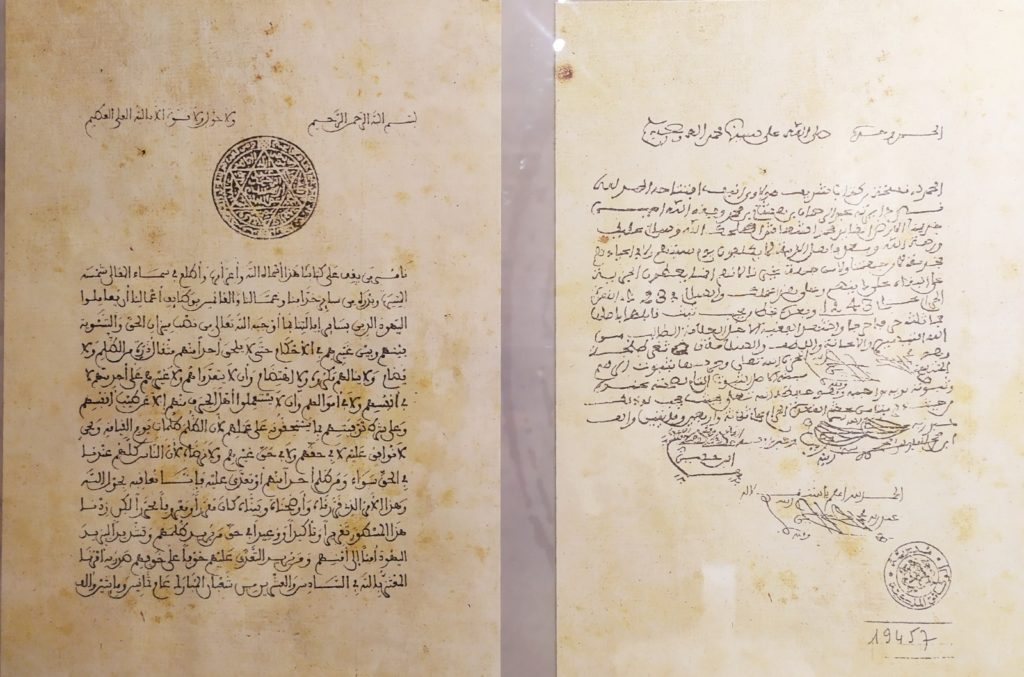

The newly inaugurated Bayt Dakira, located in the old medina of Essaouira in Southern Morocco, was praised by world-renowned figures as the symbol of a shared heritage: the heritage of Moroccan Jews. Promoted and inaugurated by the King Mohammed VI, this space shelters the historical synagogue “Slat Simon Attia”, as well as a huge collection of clothes, documents, songs, biographies and pictures, describing the richness of the Moroccan-Jewish community in one of its brightest forms.

As André Azoulay, counsellor to the King and Jewish by religion, claimed, the visit of Mohammed VI to the House of Memory “Bears the hallmark of our secular and millennial Morocco, which has known how to protect the great diversity, that is the central richness of our country”[1]. Many others, such as the French comedian Gad Elmaleh, portrayed the museum as “a message of cohesion, harmony, dialogue and entente” between the two communities, or, as Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of the UNESCO, put it, a message that “consolidates Morocco’s rich multiculturalism”[2].

The praising did not come without the widespread acknowledgment of the centrality of the King in the pursuing of the memorial preservation: Chief Rabbi David Pinto affirmed: “If we are here today, it’s because of King Mohammed VI. He is the best king in the world”.

Without any doubt, this “House of Memory” of Essaouira deserves a visit: for it constitutes an exceptionality in Morocco, in North Africa and in the Arab world. For it seeks to preserve a memory which is often forgotten, neglected, refused. For it grasps the essence of a coexistence that is previous to the Islamisation of Morocco, that shaped the history of the Cherifian rule, that contributed to the emergence of the Moroccan Kingdom, as we know it today.

While all of this is true, some questions can be raised from the official inauguration of Bayt Dakira: where are now the Moroccan Jews? Why preserving a heritage that went lost in the 1960s, with the departure of the almost-totality of Moroccan Jews? And moreover, who holds the responsibility of reviving this heritage, the Kingdom itself or his ambassadors, as Hassan II liked to define the Moroccan-Jewish diaspora around the world?

The history of Moroccan Jews: an ongoing quest for truth

The presence of Jewish communities on the territory of nowadays Morocco can be dated back to the II century B.C.; the community, initially implanted in the southern part of the country, will soon be enlarged and enriched by the immigration waves from the Iberic peninsula, after the Reconquista, thus making the Moroccan Jewish community the largest in the Arab World.

The coexistence between the two peoples, notably the Muslims and the Jews, has long been analysed and explored and has often led to the misunderstanding of the relations established between these communities: the Quranic principles leading to a specific form of acceptance of the Jewish community in Muslim societies, the specific relation established between the Amazigh and the Jews, the pre-colonial reality of a cooperation and trade between the two religious groups should not be confused with a form of equality with Muslim subjects, that the Moroccan Jews never achieved.

Indeed, it is during the French colonial occupation of Morocco that the Jews, along with the Amazigh populations, will benefit from a special form of openness towards the French educational system and language, officially recognising them as first-class citizens. In this sense, we could argue that French Protectorate of Morocco was constituted by four main groups: aside the French colons, the Moroccan society was divided along ethnic (Arab-Amazigh) and religious (Muslim-Jewish) lines.

Whereas in the precolonial era, during the historical territorial and political division between Makhzen and Dar as-Siba, the Muslim-Arab community was the sole holder of economic and cultural hegemony, the French rule adopted a divide et impera strategy which allowed the Jewish community to gain better access to economic and cultural resources – mostly through the work of the Alliance Israélite Universelle and its economic partnerships around the world. It is in this period that the division between Jews and Muslims became harsher: with the Jews aspiring to obtain French passports and thus finally become part of the “civilization” on one side, and with the Muslims promoting a religious, pan-Arab and anti-colonialist programme for an independent Morocco on the other.

Aside the cultural and historical upheaval that the French strategic choice entailed, the French domination over the Moroccan territory first represented, for the Jews – and partly for the Amazigh communities – the rising of a new cultural and political recognition. At first: the French rule in Morocco soon became embedded with the Nazi laws regarding Jewish communities, applied on the French hexagon, as well as on French colonial territories, including Morocco. It is precisely during this period that the to-be-King of Morocco, Mohammed V – although deprived of any true political power – publicly ensured his protection of the Jewish-Moroccan community, through the famous sentence: “I do not rule over Jewish subjects, only over Moroccans”[3]. This historical alignment against the Nazi persecution of the Jewish communities is remembered up to today by the Jewish-Moroccan diaspora, as they worship the Kings of Morocco as “rights among nations”.

Despite this temporary protection granted by the King, Moroccan Jews will soon be excluded from the struggle for independence: it is indeed during the 1940s that the Moroccan people asserted the Arab-Muslim character of the newly-born Kingdom, which was the only recognised identity of Moroccans according to the Constitution, until 2011, when a reform recognizing the Amazigh linguistic and ethnic heritage was upheld by Mohammed VI[4]. It is to be reminded that the fight for independence opened new channels of participation to Moroccan Jews: some intellectuals indeed fought for the independence of Morocco, aligning with far-left political formations. We may think, here, about Abraham Serfaty, Moroccan militant of Jewish faith, whose fight aligned with the communist dream of Morocco, and whose forgotten identity is embedded in the revendication of a multi-religious Kingdom.

Nevertheless, the Moroccan-Jewish community, perceived as part of the French enemy because of its closeness to the colonial power during the era of the protectorate, was almost-completely excluded from the Moroccan nation-building process; without any doubts, this exclusion was reinforced by the Moroccan aspiration to be part of the Arab-Muslim world, which was conditioned by the non-recognition of the State of Israel: in this sense, the creation of the state of Israel (1948) and the Moroccan independence (1956) constitute the two main historical facts that pushed the Jews to leave their homeland, leaving today only around 2000 Jewish representatives in the Kingdom.

The Jewish-Moroccan heritage: preserving or reviving?

The departure of the great majority of the Jews was encouraged both by the political climate of the new-born Kingdom and by the international recognition of the State of Israel. The Kingdom of Morocco is struggling to balance its international alignment between its – partly imagined – solely Arab-Muslim identity, and the striking and undeniable historical presence of a huge Moroccan-Jewish community – that also represents part of Moroccan cultural heritage and feeling of belonging to the Kingdom. Indeed, it is through music, food, literature and all other components of culture that the Moroccan Jews contributed to the birth of nowadays Morocco. The kingdom’s recent efforts, deployed at the international level, in order to be recognised as the promoter of a “moderate Islam” and “multireligious coexistence” rely on this specific feature of its history, meaning the historical presence of the hugest Arab-Jewish community on its soil.

And Bayt Dakira is nothing but the symbol of these ongoing efforts, the expression of the political will to preserve what is left of the Jewish-Moroccan community. Along with the Festival des Andalousies Atlantiques, the Festival des Musiques Sacrées de Fès, the Jewish memorial museums in Casablanca and Fez, the renovation of synagogues and Jewish cemeteries, the House of Memory embody this will to keep the “memory” of the Jewish-Moroccan community alive. Preserving, hence, without reviving. Because Morocco had to acknowledge that the vanishing of the Jewish-Moroccan community entailed the permanent loss of a living Jewish-Moroccan know-how, in music, art, jurisprudence and societal coexistence.

Preserving this heritage is, thus, a necessity to remind Moroccans, and the world, of a glorious past, of a country where Jews and Muslims used to sing together, giving birth to a new musical style, the “Musique Judéo-Arabe”; where Jews and Muslims introduced the Jellaba, now the traditional clothing of Morocco; where Jews and Muslims cooked for each other’s religious festivities, spoke the same language and worked side-by-side in the old medinas or in the villages of the Atlas.

This work of remembrance seems to represent, in this sense, the cornerstone of a new international affirmation of the Kingdom: glorifying the blossoming historical coexistence between Jews and Muslims in Morocco appears to be the backbone of a newfound political discourse, grounded on the moderate and pacific character of “Moroccan Islam” or “Islam du milieu”. Praised by the Western world as the revolutionary interpretation of a tolerant and open Islam, this religious model allowed the consolidation of the international position of Morocco. On a domestic perspective, through an increased cultural preservation of a shared heritage and the act of recognition of the Shoah – the first case within the Arab world. In the international arena the image of a moderate Islam Morocco was promoted through the strengthening Morocco’s support for the international fight against terrorism.

Today, the preservation of the Jewish heritage in Morocco is part of the emergence of a new international image of Morocco, both addressed to the Western world and the African continent, where the Kingdom seeks to assert itself as the Muslim leader of tolerance, coexistence and moderation: while enhancing the protection of its Jewish heritage, Morocco exploits the historical presence of Jews to support its project of international recognition. Preserving, thus, without reviving: because the Jews of Morocco do not exist anymore. With only around 2000 Jews living in the Kingdom, the Arab-Muslim monarchy is seeking to renovate the memory of Moroccan Jews, without being able to revive the Jewish-Moroccan culture.

Meanwhile, in Israel, something different is happening. In order to understand what, we need to remember who. Indeed, while the majority of Jews living in cities, that benefitted from the work of the Alliance, that took advantage of the French rule through jobs and education, decided to move to France, Canada and the US after the independence of the country, the Moroccan diaspora in Israel is of a whole different nature. They mostly belong, indeed, to those more ancient Jewish communities that used to share the harsh living conditions of the Atlas mountains, together with Amazigh communities: these peoples, whose history of coexistence with Muslims is documented by Hachkar in its film “Echoes from the Mellah: from Tinghir to Jerusalem”, fled the country after a long Mossad-led campaign of persuasion; they were the clients of the Israeli dream, sold by the new “Jewish State”[5].

These are the Jews that nowadays live in Israel: those who experimented a real coexistence, who left Morocco in search for the promised good life in Israel, who suffered from racism in the newly-born state, and who come back, every year, to celebrate the Moussems of their rabbis and saints in Morocco. Without museums, festivals or huge celebrations, this diaspora has been able to go beyond the preservation of the Jewish-Moroccan heritage, by reviving it in its daily struggle for recognition.

Wearing the traditional Jellaba, mixing Tamazight (the Moroccan-Berber language of the Atlas) and Hebrew, eating couscous on Saturdays and drinking the traditional sweet mint tea, the Moroccan diaspora in Israel sings the songs of the glorious past of religious coexistence of its homeland. It is a bizarre diaspora, both Arab and Jewish, both financially poor and culturally blossoming, both bi-national and subject to racism in its two homelands: this is, nevertheless, the diaspora that has been able to preserve and revive. Preserve through memory, language, music and food. Revive through new generations of Arab, Jewish, Moroccans, that anyone can meet at the airport of Marrakech or Casablanca on the eve of a holy festivity: because these Jews are the only remaining living proof of the intermingling of two religions and cultures on the Moroccan soil.

The great project of Bayt Dakira seeks to preserve [this heritage?]. Preserve, since it is important for the future generations of Moroccans to remember the origins of their moderate Islam. Moreover, this project is worthy because it keeps alive what is left of Jewish-Moroccan music, food, tales and art within a diaspora that has not failed to remind to Morocco, Israel and itself of the richness of a shared heritage? It is yet to see, whether reviving will continue to be the project of the Moroccan diaspora in Israel: it is sure, nowadays, that preserving is not enough, and reviving traditions, reinventing a historical multiculturality, upholding a shared heritage seems the only way to be a Moroccan Jew today.

[1] https://middle-east-online.com/en/moroccan-king-visits-restored-bayt-dakira-essaouira Moroccan King visits Bayt Dakira in Essaouira, “Middle East Online”, January 2020

[2] https://www.medias24.com/le-roi-se-rend-a-bay-dakira-espace-de-la-memoire-judeo-marocaine-a-essaouira-6850.html Le roi se rend à Bayt Dakira, espace de la mémoire judéo-marocaine à Essaouira, “Medias24”, January 2020

[3] https://www.cairn.info/mohammed-v-et-les-juifs-du-maroc-epoque-de-vichy–9782259187251-page-65.htm R. Assaraf, Chapter II: Mohammed V, in “Mohammed V et les Juifs du Maroc à l’époque de Vichy”, 1997 (pp. 65-84)

[4] https://journals.openedition.org/anneemaghreb/1537?lang=ar#tocto1n2 T. Desrues, Le mouvement du 20 février et le régime marocain: contestation, révision constitutionnelle et élections in Maroc, “L’année politique”, VIII, 2012: Dossier: Un printemps arabe?

[5] Kamal Hachkar, Echoes from the Mellah: from Tinghir to Jerusalem, Prod: “Les films d’un jour “(France), 2011