The Power of Humanitarian Diplomacy: Qatar’s Role in the Region

ALTEA PERICOLI

COMMENTARY #22 • NOVEMBER 2020

The changing meaning of humanitarian diplomacy

The nature of humanitarian crises is changing, and a growing number of them are frequently protracted. In these unstable scenarios, a range of different actors and donors operate at multiple levels to assist vulnerable communities and reduce the impact of conflicts on the civilian population. One of the instruments used for advocating for people in need and intervene during crises is represented by humanitarian diplomacy.

According to the definition proposed in 2007 by Larry Minear and Hazel Smith, humanitarian diplomacy can be described as: “all the activities carried out by humanitarian organizations to obtain the space from political and military authorities within which to function with integrity. These activities comprise such efforts as arranging for the presence of humanitarian organizations in a given country, negotiating access to civilian populations in need of assistance and protection, monitoring assistance programs, promoting respect for international law and norms, supporting indigenous individuals and institutions, and engaging in advocacy at a variety of levels in support of humanitarian objectives”.

The growing number of protracted crises and the changing nature of conflicts have led, during years, to a politicization of access to aid, especially in contexts fragmented and where different regional actors (state and no state ones) are involved. In these contexts, aid delivery becomes a part of the conflict itself and has to cope with the influence of internal and external stakeholders. The concept of politicization in humanitarian assistance is not new. It refers to the use of assistance for purposes that are in contradiction with humanitarian principles, such as humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence.

This aspect, together with the different nature of actors and donors involved in the humanitarian field, has created a various understanding of humanitarian diplomacy. Frequently, the same states actors involved in the conflict provide aid to the civilian population through their bilateral organizations or other forms of agencies (foundations or charity organizations). In this perspective, the meaning of humanitarian diplomacy could be declined as “the nexus between responsive activities and the diplomatic tools of negotiation, compromise and pragmatism” also used by state actors.

Qatar’s humanitarian diplomacy: which role in the region?

A relevant example of this phenomenon is represented by Qatar. Qatar’s humanitarian diplomacy has become, during years, a political instrument to influence the regional balance. It has emerged as a key actor in addressing crises in Arab, Islamic, and African States but also as a mediator in humanitarian interventions. This role has a double meaning for Qatar’s policy. As argued by Barakat Sultan – the founding director of the Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies at Doha Institute- from one side, it represents a moral obligation. Qatar’s commitment to conflict mediation is enshrined in Article 7 of its 2003 Constitution, which states that “the foreign policy of the State is based on the principle of strengthening international peace and security through encouraging peaceful resolution of international disputes”. On the other side, the role of a mediator constitutes a way to build strategic advantages.

However, to understand the Qatari foreign policy and its consequent approach to humanitarian diplomacy it is necessary to describe the regional framework in which this actor is currently shaping its image. Starting from the Arab Spring, division in ideological and political directions within the Gulf Cooperation Council has become more and more evident. With the end of Mubarak’s regime, the Saudis lost any ally against the Muslim Brotherhood, while the Qatari government supported protesters and then the newly elected Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi. The Egyptian case represents the symbol of two opposite political views in the Gulf: the Qatari approach ready to back uprisings and popular demands, in favour of the Muslim Brotherhood movement; alternatively, the Saudis and the Emirates approach aimed to preserve the ancien régime and neutralizeall those movements that could undermine its domestic political stability. The situation has not improved and since June 2017, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in partnership with Saudi Arabia, has led a coalition of states including Egypt and Bahrain in a diplomatic boycott and economic embargo of Qatar. This event strengthened political ties among Qatar, Iran, and Turkey. Doha had to survive and it found a way to pursue its independent foreign policy in the region. At the same time, the crisis influenced the approach to humanitarian diplomacy and humanitarian aid allocation.

Despite the 2017 Gulf crisis, Qatar’s role as a humanitarian donor resisted to economic and political challenges. It also gave a response to the accusations of supporting terrorism through its humanitarian interventions. The volume of the Qatari aid has not declined after 2017, but there was a shift in resource allocation with a greater portion of Qatar’s funds granted to multi-lateral organizations (43.53% of the total funds were allocated in a multi-lateral channels in 2017). This could be a sign of the Doha willing to legitimate its aid interventions, transparently allocating funds, and implementing projects with the United Nations or European agencies. Analysing data of the 2018 Annual Report of the Qatar Fund For Development, the national agencies in charge of managed foreign aid, it is possible to highlight an increasing number of partnerships with international organizations, such as OCHA, The Global Fund, UNRWA, WHO, UNDP, UNHCR, and UNICEF.

Another sign of this trajectory could be identified in a significant drop in unidentified funding, cutting them from 39.8% to 1.54% in six years. This trend has a double meaning: from one hand, in an attempt to legitimate itself through accountability and transparency, Qatar risks losing a part of its independence in aid interventions. On the other hand, it is a positive sign of collaboration between traditional organizations and this emerging Islamic donor in the region. Taking part in a multi-lateral dialogue, can foster its role of mediator and enhance its approach to humanitarian diplomacy.

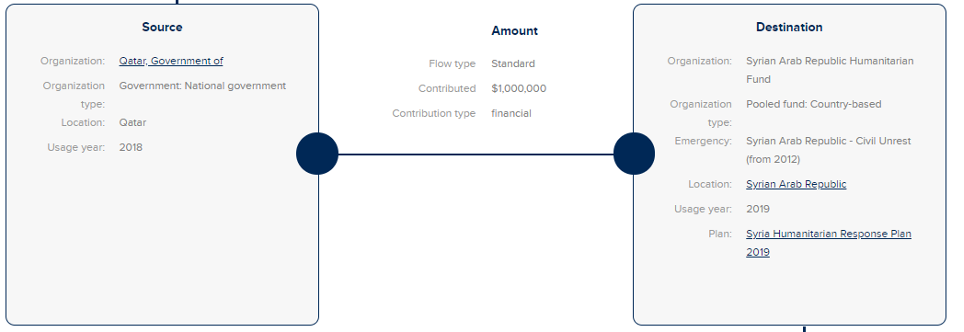

The Syrian crisis clearly shows Doha willing to maintain its position as a humanitarian actor in both an independent and international tied approach. The Qatar Fund for Development, in 2018, signed several agreements to finance emergency response projects in the country through Qatar Charity and Qatar Red Crescent Society. At the same time, it is in partnership with OCHA, for instance, for financing and implementing projects. In the same year, the Qatar government contributed $ 1 million to the Syria Humanitarian Response Plan, a framework within which the international community can respond to the humanitarian needs of the Syrian population. Its structure is based on a prioritization of sectors and funding requirements to address needs.

Conclusion

In a changing humanitarian scenario, the awareness about the policies and approaches of emerging donors results essential to define the new relations between traditional and new actors. Considering that a growing number of crises occur in the Middle Eastern and Muslim African countries, it is clear how import is to understand trajectories and approaches of Islamic actors and donors which operate in crisis contexts alongside traditional ones.

Qatar’s intervention in the humanitarian and development framework and its approach to humanitarian diplomacy play an important role in the regional area, due to its political independence and strong activism in financing and implementing aid. Its attempt to legitimize itself and collaborate with UN agencies and other international organizations could be a positive sign to enhance the dialogue among actors from different “cultural lines-up,” that often work at the local level in a mutual mistrust, in order to avoid the polarization of aid and fill the financial and logistic gap of emergency and development relief. In other words, Qatar should maintain its independence in elaborating aid policies and humanitarian diplomacy and, at the same time, enhance the dialogue with international institutions.

References

Barakat, Sultan. “Priorities and challenges of Qatar’s Humanitarian Diplomacy”, Chr. Michelsen Institute, 2019. https://www.cmi.no/publications/6906-priorities-and-challenges-of-qatars-humanitarian-diplomacy

Barakat, Sultan. “Qatari Mediation: Between Ambition and Achievement”, Brookings Doha Center Analysis Paper N. 12, Brookings Doha Center, 2014.

Barakat, Sultan & Milton, Samson. “Qatar as an Emerging Power in Post- Conflict Reconstruction and Conflict Mediation”, in Paczynska (ed.) Emerging Powers and Post-Conflict Reconstruction. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

De Lauri, Antonio. “Humanitarian Diplomacy: a new research Agenda”, Chr. Michelsen Institute, 2018. https://www.cmi.no/publications/6536-humanitarian-diplomacy-a-new-research-agenda

Financial Tracking services, OCHA, 2020. https://fts.unocha.org/countries/181/flows/2018.

Kaussler, Bernd. “Tracing Qatar’s Foreign Policy Trajectory and Its Impact on Regional Security”. Report. Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep12689.

Smith, Hazel Anne, and Larry Minear. “Humanitarian diplomacy: Practitioners and their craft”. United Nations University Press, 2007.

Qatar Fund For Development. “Annual Report 2019”, 2020. https://qatarfund.org.qa/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2019-annual-report-en-v23.pdf

Qatar Fund For Development. “Annual Report 2018”, 2019. https://qatarfund.org.qa/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/QFFD-Annual-Report-2018-May-2.pdf

Régnier, Philippe. “The emerging concept of humanitarian diplomacy: identification of a community of practice and prospects for international recognition.” International Review of the Red Cross 93.884, 2011, 1211-1237.