These Memes Explain the Protests in Lebanon

IBRAHIM AL-MARASHI, The Square Advisory Board Member

TRT World | October 22, 2019

The protests in Lebanon are spontaneous but these memes show their origins have been the butt of jokes for a long time.

Spontaneous protests erupted across Lebanon last Thursday, initially triggered by the government’s plan to impose a tax on the messaging app WhatsApp, and after it failed to adequately respond to recent wildfires that ravaged the nation.

However, the underlying reasons for the protests are embedded in the failure of the Lebanese state to provide reliable governance and services for decades.

While Lebanon has never undergone a state-led conflict resolution process on a macro level since the end of major fighting in 1990, the Lebanese have endured micro-conflicts on a daily basis since, navigating corruption in bureaucracies, or enduring unreliable services ranging from water, electricity to waste collection.

Prior to the protests, a series of memes highlighted these structural problems as well as a political elite unable to meet the basic quotidian needs of their constituents.

The quest for services

Reliable electricity has been elusive for Lebanon’s population, demonstrated by the following meme from the Lion King. It features the following dialogue: “Look, Simba. Everything the light touches is the land of the humans.”

When Simba asks about the shadowy place, he is told, “That’s Lebanon. They have no electricity.. never go there Simba NEVER.”

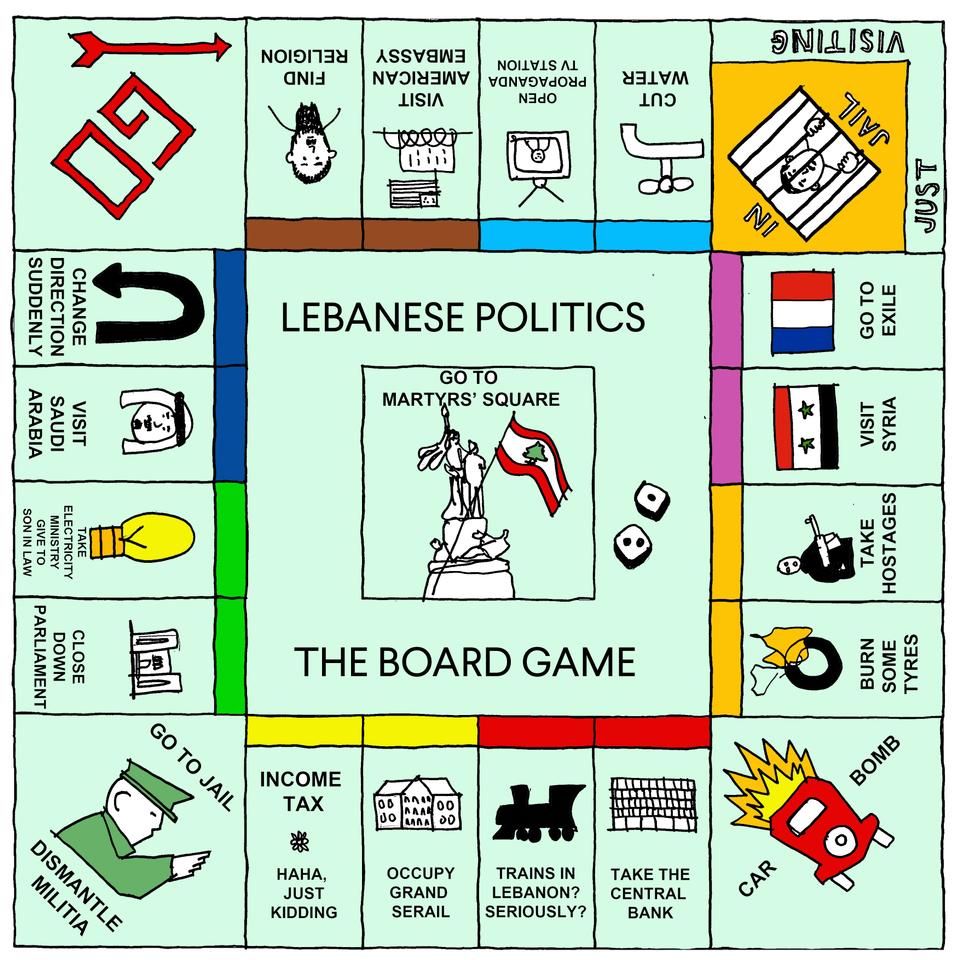

A similar theme relating to electricity is addressed by Lebanese architect and satirist Karl Sharro in a series of memes that captures the ethos of the nation’s frustrations well before the protests erupted.

In a November 2012 meme, “Lebanese Politics: The Board Game,” one of the squares in the faux Monopoly board reads “Take Electricity Ministry Give to Son in Law.”

That is a reference of course to the clientist capture of Lebanese ministries by the political elites, and the reference to “Cut Water” is another caustic reminder of the state’s failure in delivering reliable services.

The game also summarises how Lebanon’s political class is ill-equipped to tackle the protesters’ demands, hence why some declared their desire for “isqat al-nizam” or “the end of the system.”

While Lebanon’s cabinet announced on Monday reforms to appease the demonstrators, the protesters realise that the embedded problems cannot be addressed by cosmetic changes announced in a single government session.

Lebanon’s political class

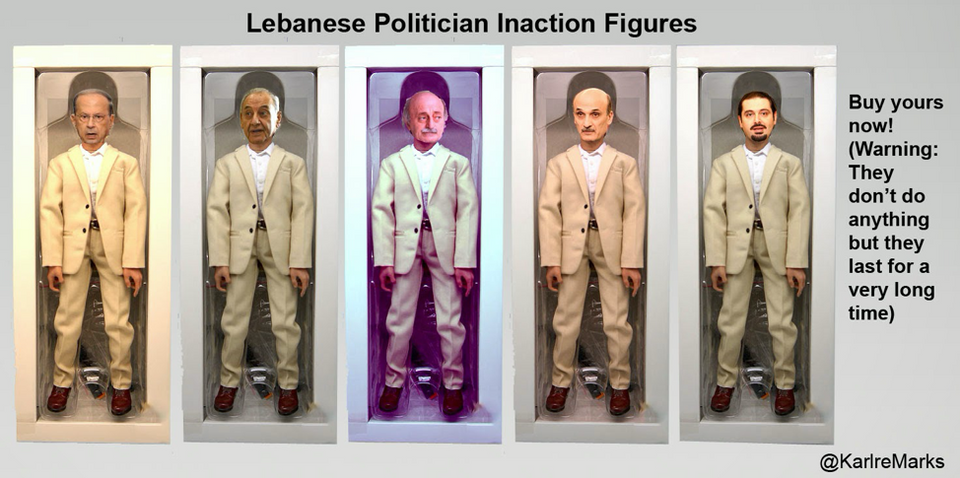

The frustration with Lebanon’s rulers is highlighted by Sharro’s 2014 memes “Lebanese politician inaction figures,” which he writes, “They don’t do anything but they last for a very long time.”

The faces range from Lebanon’s current prime minister Saad Hariri to Walid Jumblatt, leader of the Lebanese Druze population and of the Progressive Socialist Party, one of the numerous factions that took part in the nation’s civil war from 1975 to 1990.

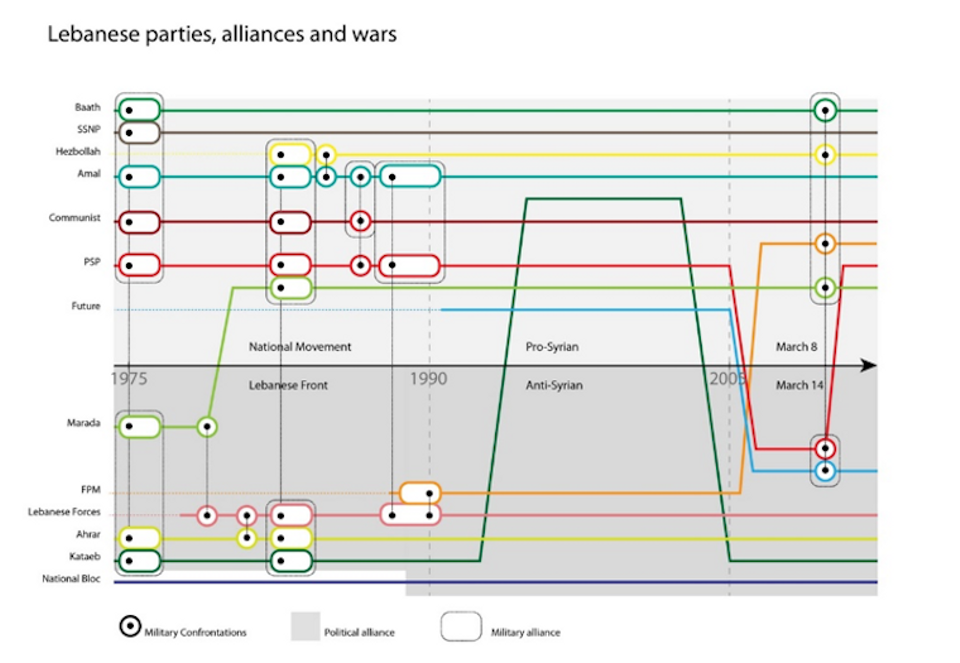

A chart from Sharro that is not meant to be satirical demonstrates the parties on the eve of the Lebanese civil war in 1975 until the 21stcentury, illustrating that the factions never went away but rather the leaders changed their army fatigues for suits and entered the political process.

His chart also repudiates the binary of the civil war beginning as a clash between the nation’s Christians versus Muslims, highlighting the intra-Christian fighting in the seventies or intra-Shia fighting in the eighties.

The chart raises a vexing question: has the Lebanese civil war ended?

A meme that came out during the protests declared that the war officially ended on 20 October 2019.

The declaration that Lebanon’s civil war has come to an end relates to the protesters that transcend sect and religion, similar to the recent protests in Iraq.

The end of the civil war?

Memes and satirists like Sharro were able to capture widespread frustration in a single image and anticipate the protests better than pundits because political humour only works if the joke holds resonance with its target.

Satire serves as a window to reality. Sharro’s work revealed the institutional legacies from the Lebanese civil war, including municipal infrastructure that never was rebuilt adequately and a political class that emerged from the battles in the streets to fight it out in the halls of parliament.

Politically satirical memes serve as digital artefacts that are useful to historians seeking to understand the recent past to understand the present better.

Indeed, I have used Sharro’s memes and charts to teach both Lebanese and non-Lebanese generation Z students the complexities of governance in post-conflict nations and to undo sectarian and religious binaries that are often imposed on the region.

The protests are also expertly unravelling these binaries.